The Seven Canoe Men

In 1750, in the time of the Transatlantic slave trade, a Norwegian captain of a Dutch slave ship was put on trial in Amsterdam for … human trafficking. He was accused of seizing Africans and selling them into slavery in Suriname.

The canoe men were highly skilled individuals whose services were sought along the West-African littoral. Heavy surf and dangerous cliffs made their job perilous, but they provided the fastest link between coastal communities and between the shore and visiting ships.

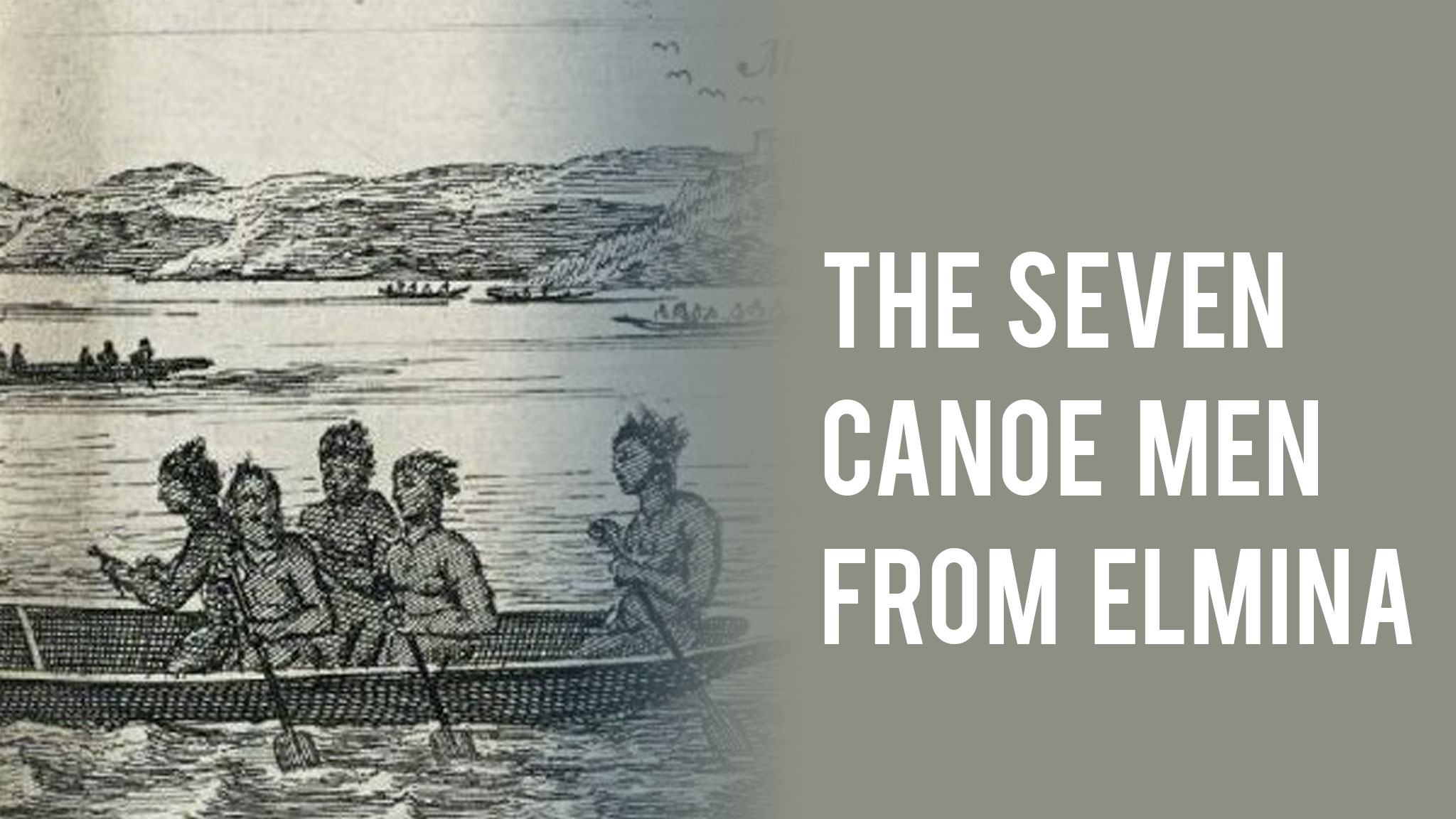

In 1746 Norwegian captain Christian Hagerup visited the Gold Coast to acquire enslaved individuals for the plantation colony of Suriname in South America. His ship, a Dutch vessel named Africaen, anchored near fort Batestein (Butre, Ghana) on 21 May.

Hagerup was dissatisfied with the European factor of the fort, who had failed to deliver enough enslaved individuals in time. The captain decided to seize seven African canoe men hired by the factor to paddle between the ship and the fort. Before anyone on the shore could react, Hagerup set sail for Suriname. After he arrived there in July of 1746, he sold about 300 enslaved men, women and children to local plantation owners, including the seven canoe men.

Back in Africa, friends and family of the kidnapped men were furious. They went to the main Dutch fort on the Gold Coast and demanded action. Out of self-interest, the head of the Dutch company promised to do everything within his power to bring the men back from slavery. Three long years passed, before the governor of Suriname was instructed by his principals to look for the missing men in his colony. An agent of the West India Company visited plantations to look for the Africans. Most planters were suspicious and unwilling to cooperate.

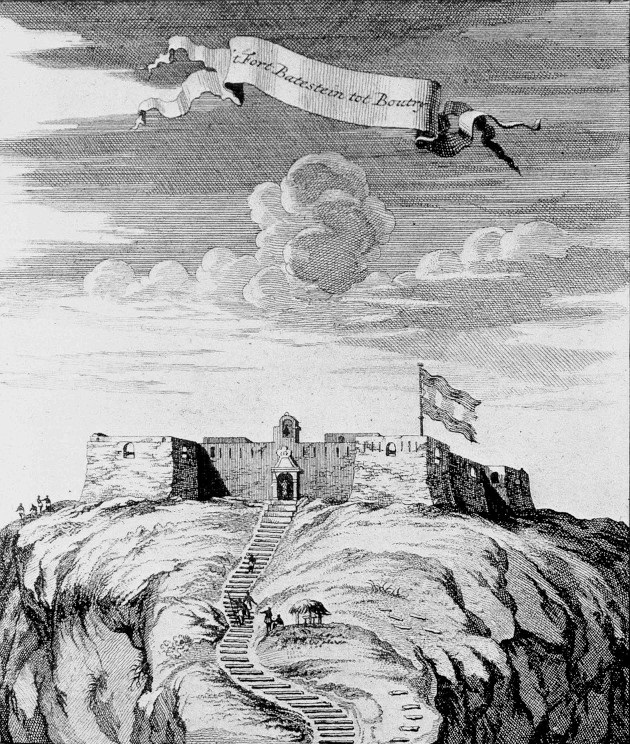

The agent had a hard time finding the canoe men. He wrote that most planters had no idea of the original names of the enslaved Africans they bought, and just gave them new names. In this case, the real identity of the canoe men was crucial to locate them. Kakera Acotie and Cobena Manson were found quickly, but the former was too ill to travel and the latter refused to leave his compatriot. As they waited to travel to Amsterdam, the company agent found the other missing canoemen. It turned out Atta had died in slavery. In September 1749, the African men reached Amsterdam. They stayed for seven weeks, waiting for a ship to the Gold Coast. One of them, probably Kakera Acotie, needed 12 visits to a doctor to treat an illness. Nevertheless, he died en route to Africa.

Finally, in March 1750, the surviving five canoe men returned home, which led to “inexpressible joy” among friends and family. The West India Company paid reparations to the kidnapped canoe men. They also made sure Hagerup was arrested as soon as he set foot in Amsterdam. Dutch lawyers argued that Hagerup was guilty of abducting free people into slavery. The captain admitted to kidnapping the canoe men, but added that he thought they were already enslaved. The case shows some uneasiness with slavery in the Dutch Republic in 1750. Lawyers even argued that “slavery under European peoples is considered abominable and is being reduced, and also by the Dutch practiced and tolerated in their colonies only out of necessity”.

Still, slavery continued to be legal in Dutch colonies for more than a hundred years after this case. Hagerup spent half a year in jail, but received little additional punishment. He went on to become a captain with the Dutch East India Company. The Hagerup case was not a case against slavery in general. In fact, the directors of the West India Company wanted to prosecute the captain so they could continue trading in enslaved humans. They needed good relations with the people who lived near their forts.

About the author:

Gerhard de Kok: Diving into data-driven historical research. Excited about AI, good stories and Mexican food. PhD, Leiden University. Historian and programmer.

Twitter handle: https://twitter.com/gerharddekok?s=20